Every righteous person matters

In this week’s Torah portion, Vayera, God decides to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, because “their sin is so great.”

Later in the parsha we’ll see an example of their sin: an angry mob demanding that Lot release the strangers whom he’s protecting, so that the mob can rape them. That’s one way to read the sin of Sodom and Gomorrah: their response to strangers is violent domination.

Here’s another, from the prophet Ezekiel: “This was the guilt of your sister Sodom: arrogance! She and her daughters had plenty of bread and untroubled tranquility, yet she did not support the poor and needy.”

But before that happens, Abraham argues with God: what if there are fifty righteous people there? Or forty? And he bargains God down, and God agrees that if a single minyan of tzaddikim can be found, the cities will be spared.

This year we’re reading these verses against the backdrop of election aftermath. We’ve all been on tenterhooks waiting for votes to be counted. Maybe feeling afraid of violence or afraid for our nation.

And here’s Abraham saying to God: wait, even if You’re despairing, count everybody. Here’s what I take from that passage this year: every righteous person counts. Every righteous person makes a difference. Even if we may feel insignificant in the big picture — every one of us who is trying to do what’s right, matters.

Many translations of this dialogue between Abraham and God about Sodom and Gomorrah use the terms “guilty” and “innocent,” e.g. “Far be it from You… to bring death upon the innocent as well as the guilty, so that innocent and guilty fare alike!” In that translation, Abraham is urging God to remember the people who are innocent of wrongdoing.

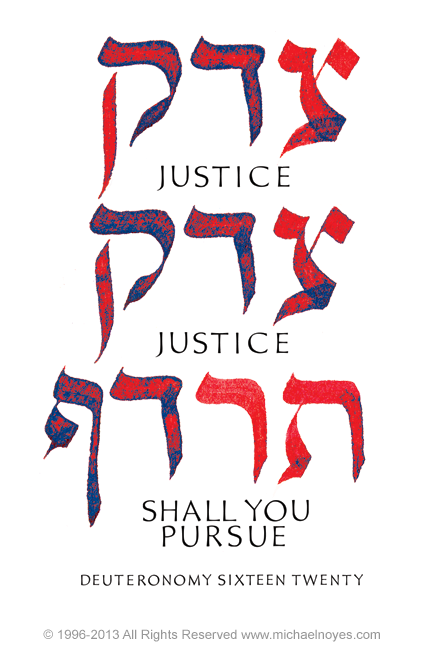

But I would argue that the plain meaning of the Hebrew words rasha and tzaddik is stronger than that. A rasha is someone who acts wickedly. Some say: a rasha is concerned only with themself and their own needs, rather than the needs of the community or the needs of the vulnerable. And a tzaddik isn’t just “innocent.” A tzaddik is someone who acts righteously — someone who acts with tzedek, justice.

And what is righteous behavior? Judaism has a lot of answers to that — we have 613 instructions, for starters! But here’s a shorter list. Righteousness means loving the stranger — feeding the hungry — caring for the widow, the orphan, and the stranger, in other words the powerless and vulnerable — seeking justice with all that we are. That’s our work. That is always our work.

And it’s not always easy. Sometimes it feels like an uphill battle. The pastor John Pavlovitz writes,

“There is a cost to compassion, a personal price tag to cultivating empathy in days when cruelty is trending… Friend, I know you’re exhausted. If you’re not exhausted right now your empathy is busted. But I also know that you aren’t alone.”

For those of us who trust science, it’s exhausting to know that so many of our fellow Americans think masks infringe on their civil liberties — or think covid is a hoax. Especially in a week with days where the US kept breaking our own records for new covid-19 infections: first 100,000, then 109,000… And that’s just one reason to feel exhausted. Election uncertainty is exhausting. Fears of violence are exhausting.

But in this week’s parsha what I hear Abraham saying is: don’t give up. We need to keep doing the right thing: it matters, it makes a difference, even if we don’t know it. We need to be tzaddikim. We need to keep loving the stranger, feeding the hungry, caring for the needy and the vulnerable, pursuing justice. Wearing our masks. Protecting the marginalized. Feeling empathy for others. Counting every vote.

This is our obligation as Jews — as citizens — as human beings. This was our work before the election; this is our work after the election. And yeah, this is hard work. Most things worth doing are.

Maybe there weren’t ten tzaddikim in Sodom, but I believe there are tzaddikim everywhere. And if we’re trying to act justly in the world, our work matters — our work counts.

May Shabbat bring balm to our bruised and anxious hearts… so that when the new week begins, we can bring renewed energy to the work of doing what’s right, the work described in the Langston Hughes poem that was our haftarah reading today, the work of building a better world.

This was Rabbi Rachel’s d’varling from Shabbat services this morning (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)