In this week’s Torah portion, Va’era, God hears the cries of the Israelites and promises to free us from bondage. But when Moshe comes to the children of Israel to tell them that, Torah says:

וְלֹ֤א שָֽׁמְעוּ֙ אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֔ה מִקֹּ֣צֶר ר֔וּחַ וּמֵעֲבֹדָ֖ה קָשָֽׁה׃

They did not hear Moshe, because of kotzer ruach and hard servitude.

Rashi explains the phrase kotzer ruach by saying, “If one is in anguish his breath comes in short gasps and he cannot draw long breaths.” For the Sforno, kotzer ruach means “it did not appear believable to their present state of mind, so that their heart could not assimilate such a promise.”

So which one is it, a physical shortness of breath or a spiritual diminishment that keeps hope beyond our grasp? Of course, the answer is both. Body and spirit are not separable. If you’ve ever had a panic attack, you know the feeling of being physically unable to breathe because of an emotional or spiritual reality.

Kotzer ruach means that we were short of breath in body and soul. Our breath and our spirits were in tzuris, suffering. Literally at this point in our story we are in Mitzrayim (hear that same TzR /צר sound there?) But this isn’t about geography, it’s about an existential state of being so constricted that we couldn’t even hear the hope that things could be better than this.

I know a lot of us are navigating heightened anxiety these days. A scant ten days ago, an armed mob refusing to accept the results of November’s election broke in to the US Capitol with nylon tactical restraints and bludgeons. Many members of that mob proudly displayed neo-Nazi or white supremacist identities.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the attack on the Capitol wasn’t spontaneous, but planned. The FBI is warning now about armed attacks planned in all fifty state capitols and in DC, on inauguration day if not before.

The covid-19 pandemic worsens by the day. We keep breaking records for number of sick people and number of deaths. Meanwhile the integrity of our country feels at-risk. I mean both our capacity to be one nation when some portion of that nation refuses to accept electoral defeat, and our moral and ethical uprightness.

Anybody here feeling kotzer ruach? Me too.

And… Our Torah story comes this week to remind us that kotzer ruach is not the end of the story. Being in dire straits — unable to breathe, unable to focus, hearts and souls unable to hope — is not the end of the story. On the contrary, it’s the first step toward liberation.

In our Torah story, our kotzer ruach causes us to cry out. That’s where this week’s Torah portion begins: with God saying hearing our cries and promising to help us out of narrow straits. If you have a prayer practice or a meditation practice or a primal scream practice, now is the time to cry out. (And if you don’t have such a practice, now is a good time to start.)

I don’t actually believe that God “needs” us to cry out before God takes notice of us. I think it goes the other way. We need to cry out, because that’s the first step in opening our hearts to God — to hope — to the possibility that things can get better.

The path toward the pandemic getting better is pretty clear. We shelter in place as best we can, we stay apart, we wear our masks, we get the vaccine. And then we probably keep wearing our masks. But in time, it will be safe to gather again outside of our household bubbles. In time, we will be able to gather in community, and sing together without risk, and embrace.

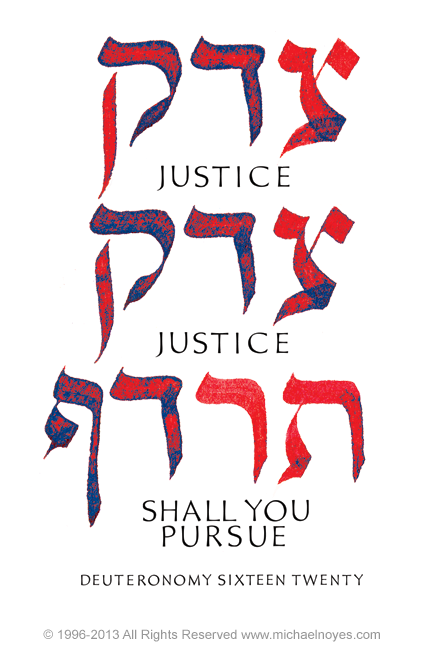

The path toward restoring the integrity of our nation is less clear to me. I think it involves accountability, and justice, and truth, because I think integrity always asks our commitment to those ideals. Regardless, we begin that journey from here, where we are, crying out with our anxious and broken hearts.

We’ve entered the lunar month of Shvat, known mostly for Tu BiShvat, the New Year of the Trees, which will take place at the next full moon. The full moon after that brings Purim. And the full moon after that brings Pesach, festival of our liberation. These three full moons are our stepping-stones to spring, and change, and freedom.

When I was working recently with the rabbis and poets and artists of Bayit on new liturgy for Tu BiShvat, one of my colleagues said something that moved me so much I wrote it on a post-it and stuck it to my desk. I wrote,

“Karpas dipped in tears — like the tears that water our new growth.”

Karpas is the spring green we dip in salt water during the seder. The salt water represents the tears of our enslavement, the tears of feeling stuck in kotzer ruach. For us this year those might be tears of grief at covid-19 deaths: 381,000 and counting. They might be tears of grief at how far our democracy has fallen from its ideals, or tears of fear for whatever may be coming.

Our tears can water new growth of heart and soul. Our heart’s cry now is the first step toward the changes that will lead to liberation. Then we will fulfill the words of the psalmist: “Those who sow in tears will reap in joy.” Kein yehi ratzon.

This is Rabbi Rachel’s d’varling from Shabbat services at CBI (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)

Illustration, by R. Allie Fischman, from Connections: Liturgy, Art, and Poetry for Tu BiShvat, Bayit, 2021.