“…The thing is, there’s holiness in the not-knowing. There’s holiness in opening ourselves to the uncertainties of wilderness. It’s no coincidence that our ancestors hear God’s voice most clearly in the wilderness. The midbar (wilderness) is where God m’daber (speaks) — or at least, where we hear….”

In this week’s Torah portion, Yitro, we receive Torah at Sinai. Tradition teaches that every Jewish soul that ever was and ever will be was present at Sinai. At Sinai we stood together as one.

This week some of you have told me that you feel more connected than usual to Jews in other places… especially the Jews of Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville, Texas. That their shul shares our name heightens our sense of closeness.

Last Shabbat while members and the rabbi of that CBI community were held hostage, our hearts were in our throats and our prayers flowed without ceasing. Often a crisis makes us aware of the interconnectedness we usually don’t see. In a crisis, it’s easy to feel how what happens to one heart tugs at another heart, bound up as we are in what Dr. King called that “inescapable network of mutuality.”

What happens to you impacts me. What happens there impacts us here. That’s one of the continuing lessons of the pandemic. And this week, our connectedness means that many of us share a feeling of renewed vulnerability.

But we’re connected not only because of our shared vulnerability, our shared fears of antisemitism and attack. We’re connected because our souls stood together at Sinai. We’re connected through mitzvot. In Aramaic, Hebrew’s closest sister tongue, the word for connection is tzavta, which shares a root with mitzvah. The mitzvot connect us with God and with each other.

Some of those mitzvot are listed in this week’s Torah portion. Be in relationship with the Force of Liberation bringing us forth from life’s narrow places. Resist the urge to worship things that are not God, like statues or status. Remember the day of Shabbat and keep it holy, because when we pause our constant making and doing we are re-ensouled.

And some of the mitzvot our tradition holds dear aren’t in today’s list, because our tradition is comprised of 613 commandments, not just 10. For instance, the mitzvah repeated thirty-six times in Torah, instructing us in no uncertain terms to “Love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” The rabbi at CBI Colleyville lived out that mitzvah when he invited an unknown man in on a twenty-degree morning and made him a cup of tea to help him get warm. We all know now how that turned out. And: I still think he was right to do it. Welcoming that stranger was the Jewish thing to do.

How do we do that in a way that keeps us safe as a community? That’s a big conversation, and it’s one we’ll be having for a while. There’s no simple answer to balancing the Jewish value of pikuach nefesh (protecting or preserving life) with the Jewish value of hachnasat orchim (welcoming others in hospitality). It’s another version of the core spiritual balancing act to which our tradition calls us, between gevurah and chesed — boundaries and lovingkindness.

It’s okay to feel afraid. It would be spiritually dishonest to pretend otherwise. When someone chooses to join the Jewish people, at the end of their beit din and just before immersion there’s a ritualized series of questions rooted in Talmud that I ask. They’re questions like: don’t you know that it’s sometimes hard to be Jewish? Don’t you know that being Jewish comes with obligations, and yeah, it also comes with antisemitism that will now be aimed at you?

But today I want to add: don’t you know that being Jewish is also joyous? Lighting Shabbat candles and letting the week’s worries slough away — telling our core story of liberation at the seder with songs and laughter — the heart-opening and mind-expanding journey of Jewish learning — feeding the hungry and clothing the naked and caring for the powerless — there’s so much beauty and meaning here.

All of these connect us with our cousins in Colleyville, and Squirrel Hill, and Poway, and all over the world. Antisemitism is real and it’s frightening and it probably isn’t ever going away. But the mitzvot, and our Jewish joy — they can’t take that away from us.

The commentator Rashi notes that when Torah describes our encampment at Sinai, it uses a singular verb to teach us that when we gathered at the base of that mountain we were like one being with one heart. We get another hint toward this a few verses later, where we read that the whole community answers יַחְדָּו֙ / yachdav, as one.

It’s easy to focus on all the things that divide us: different Jewish denominations, different ways of doing Jewish, different dress codes, different relationships with mitzvot or God or spiritual practice. But at Sinai we had a shared heart. And during last weekend’s crisis we felt our shared heart. May the shared heart that we felt while our cousins in Colleyville were in danger stay real for us, long after that danger is gone. And may that shared heart connect and sustain us through whatever comes.

This is the d’varling that R. Rachel offered at Kabbalat Shabbat services this week (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)

In this week’s Torah portion, Bo, we are deep in the story of the plagues and traumas that unfolded as a prelude to yetziat Mitzrayim, our Exodus or going-forth from the Narrow Place.

The Hasidic master known as the Me’or Eynayim teaches that our spiritual ancestors were so overwhelmed by the hardship and servitude of Mitzrayim that they lost דעת / da’at, knowledge or awareness of God.

Part of what was so painful about Mitzrayim, he says, is that we lost access to our spiritual practices and our traditions. Maybe we had a vague sense that those things had meant something to our ancestors, but we weren’t living them. So our awareness of God atrophied like an unused muscle.

When we were in Mitzrayim, says the Me’or Eynayim, our דעת / da’at (awareness) was בגלות / in galut (exile) and בקטנות / in katnut (smallness). Our awareness of God went into exile, our awareness of God became diminished. And then he says something that really leapt out at me, reading it this year: it’s as though God says to us, התקטנתי במצרים — “I made Myself small in Mitzrayim.”

As though when our lives contracted, God’s own self contracted too. When we are in Mitzrayim, it is as though God shrinks. When we are in tight straits, when our hearts and souls feel constricted, when our lives feel constricted, it’s as though God becomes smaller. When our awareness of God atrophies, it’s as though God actually shrinks. Wow: this year, that teaching really speaks to me.

There’s a website called What Day Of March 2020, and if you go there, it will tell you that today is the 680th day of March 2020. As though time stopped when the pandemic began for us, and that month of March has lasted forever. It’s a joke, and it’s also not a joke.

Between the Delta variant and the Omicron variant, earlier this week there were more than a million new COVID cases. We’re facing our third pandemic Purim, our third pandemic Pesach. Hospitals everywhere are filling up again. We are all tired of this. And it is nowhere near over yet.

Right now the pandemic is our Mitzrayim. These are some tight straits. Maybe our hearts and souls feel constricted. Maybe we’re exhausted or overwhelmed or afraid. And when we are in tight straits it’s natural for our awareness of God, our sense of where we fit into the Mystery of the cosmos, our capacity to hope to become diminished. For us as for our ancestors, it’s as though God becomes smaller.

That could also be a description of what it feels like to grapple with depression. Awareness of God diminishes, capacity to hope diminishes, connectedness to what sustains us diminishes, sense of Mystery diminishes — it’s as though God becomes smaller. This teaching resonates on that level, too… though this isn’t just a time of personal Mitzrayim, it’s a time of communal Mitzrayim.

This week’s Torah portion, and this commentary from the Me’or Eynayim, arrive at just the right time. They’re here to remind us that even when we feel like we’re in galut in Mitzrayim, exiled in these tight straits, our spiritual task is to trust in yetziat Mitzrayim, to trust in the Exodus. Our work is to cultivate our capacity to feel in our bones that life will not always be like this. That’s a big leap of faith.

I think it’s a necessary one, if we want to get through this pandemic spiritually intact. Our work is to strengthen our da’at, our awareness of God. If the “G-word” doesn’t work for you, try: our awareness of hope, of love, of genuine justice. Because when we strengthen our da’at, we strengthen our capacity not only to trust that better days will come, but also to work toward those better days together.

Offered with endless gratitude to my hevre at Bayit, with whom I’m studying the Me’or Eynayim.

This is the d’varling that Rabbi Rachel offered at Shabbat morning services this week, cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.

This week’s parsha is Vayechi, “He lived.” It opens, “Jacob lived seventeen years in the land of Egypt, so that the span of Jacob’s life came to one hundred and forty-seven years.” (Genesis 47:28) As with Chayyei Sarah (“The Life of Sarah”) earlier in Genesis, this parsha named after someone’s life is actually about their death, because only at the end of a life can its wholeness be measured.

Joseph brings his sons to their grandfather’s bed, and Jacob asks, “Who are they?” Maybe he doesn’t recognize them. Maybe he knows they’re related to him, but just can’t recall their names. Joseph says, “these are my sons, whom God has given me here.” I like to imagine that his voice and demeanor are gentle. It’s okay that you don’t remember; I can tell you who they are.

I learned the term “benign senescent forgetfulness” from John Jerome z”l in his book On Turning Sixty-Five: Notes from the Field. As a writer and a runner he was fascinated by the effects of aging on body and mind. Benign senescent forgetfulness is the natural tendency of the human brain to start losing track of things. It’s normal. As we age, some of what’s in our brain just… falls out.

Of course, memory loss can become disabling. I wonder how Jacob handled his inability to remember his grandsons. Did he get frustrated by the mental holes where knowledge used to be? More broadly: could he take comfort in memories of his wives and children, his travels and adventures — or did disappointments and losses take center stage as other memories slipped away?

Sometimes memory loss sparks paranoia. Because the world doesn’t feel right, and words and memories aren’t within reach, elders with dementia often lash out at their children or caregivers. That came to mind this year when I read Jacob’s parting words for each of his sons. Some of those words are loving and kind; I like reading those. But some of his words seem belligerent, even cruel.

In Jacob’s case, given what we know of his children’s lives, some of his anger may be justified. For instance, he accuses Shimon and Levi of violence. I can understand where that’s coming from, because they did make violent choices. He intimates that Reuben encroached on Jacob’s marriage bed with Bilhah, which may be supported in Torah – though some commentators disagree.

What jumps out at me is how common that accusation is. My grandfather z”l levied a similar accusation near the end of his life. (Women often accuse their children or caregivers of stealing their things.) We all knew it wasn’t true; it was dementia clouding his mind. But it’s still painful to hear words like those, especially from someone who had previously been generous of spirit.

This year I wonder: how did Jacob’s deathbed words land with his grown children? Did they find any comfort in the knowledge that some of these words might have been rooted in dementia? And is it fair to blame the curses on dementia while holding on to the blessings that accompanied them? Because some of what Jacob says at the end of his life is gentle and tender!

He compares Judah to a mighty lion; Naftali to a beautiful deer; Joseph to a colt strengthened by God. And to his grandsons Ephraim and Menashe he offers a poignant blessing, saying, “May the angel who keeps me from harm bless the ones who come after!” (That’s R. Irwin Keller‘s singable translation.) And then Jacob pleads, “In their name, may my name be recalled.” (Genesis 48:16)

You may recall that he had two names: Ya’akov, “the Heel,” and Israel, “God-wrestler.” Remembering his names means remembering the whole: the shrewd young trickster, and the patriarch changed by his wrestle with God, and all of his roles and identities in between. When we look at the whole of Jacob’s life in this way, I think it’s easier to have empathy for how his story ends.

I do think it’s okay to blame the curses on dementia while holding on to the blessings. For me, the blessings come from a true place. They come from a heart flowing with love that wants to bestow that love on the generations. The bitter words or curses come from a false place, a mind clouded by confusion. I believe that the loving words are real, and the hurtful words aren’t.

And what about us, “the ones who come after?” We’re called to compassionate memory. When we remember all of who he was, his “name is recalled in us.” Our task is to recall the choices and adventures and accomplishments of our patriarch’s lifetime. To hold with compassion the whole of his story: the beginning and middle that came before this runway toward an end.

This is the d’varling R. Rachel offered at CBI at Kabbalat Shabbat services (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.) Art by Yoram Raanan.

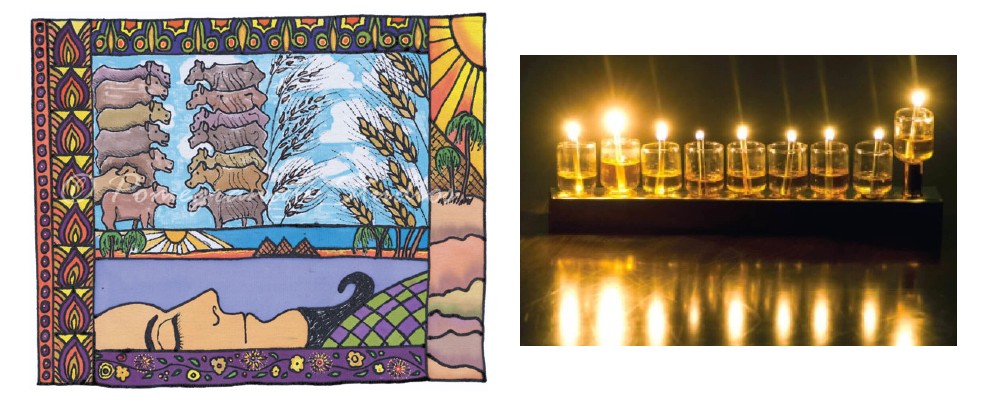

Pharaoh’s dreams (artist unknown); an oil-lamp chanukiyah.

This week we continue the Joseph story. In this installment, Pharaoh has two disturbing dreams. In one dream, seven happy fat cows emerge from the Nile, followed by seven emaciated cows who eat the fat ones. In the other, the same thing happens with ripe ears of corn and shrunken ones.

No one in his court can interpret the dreams. And then the cupbearer pipes up: I was in your prison a while back, and there was a Hebrew prisoner who interpreted dreams! So Pharaoh sends for Joseph, who says, the dreams mean that seven good years are coming, followed by seven years of famine.

Joseph tells Pharaoh to set someone wise in charge of his storehouses, someone who can save during the years of plenty so there will be food to eat in the lean times. Pharaoh promptly promotes him, saying, “Could we ever possibly find another man like him, a man in whom is the spirit of God?”

(Or in the words of Lin-Manuel Miranda, “Hey yo, I’m gonna need a right-hand man.”)

Pharaoh’s dreams are about guarding our resources. When there is abundance, set some aside and save it for when there won’t be. And this isn’t just about individual households saving what they can; Joseph sets aside grain for the whole nation, so the government can make sure everyone makes it through.

Every year, we read this at Chanukah. As my b-mitzvah students learned this week, there are different stories we can tell about Chanukah. One is the story of oppression and war in the books of Maccabees — which were not canonized into the Hebrew Bible, though they are part of some Christian Bibles.

Another is the story of the sanctified oil that lasted for eight days. That narrative comes to us from Talmud, and it’s the one our tradition chose to enshrine. That Chanukah story is a story about hope, and enough-ness, and the leap into faith when we don’t feel like we have enough fuel to keep hope burning.

Sometimes we feel like we don’t have enough. Maybe we feel that we ourselves aren’t enough. Maybe life feels overwhelming, and in the words of the poet William Stafford, “The darkness around us is deep.” The Chanukah story asks us to kindle light exactly then. That’s when we need hope most.

This week Torah says: don’t use everything up — resources are finite! Save some of what you have so you can help everyone make it through the lean times! Meanwhile the Chanukah story says: kindle the eternal light, even if you’re going to run out of oil! So which one is right? They both are.

The Torah teaching is about things we can touch: protecting our natural resources, not eating all the grain, making sure we can feed people when there’s famine. The Chanukah teaching is metaphysical: it’s not about oil, but about hope. It’s about kindling hope in our hearts, and keeping hope burning.

Earth and water and air and trees and food are finite, and we need to steward them carefully and share them equitably — that’s a big one, we’re working on that. But hope provides its own fuel. And like love, it doesn’t diminish when we share it. Being a Jew — for me — means living up to both of these truths.

We need to be wise with our resources, and help people who live at sea level, and nations that don’t yet have enough vaccines. That’s never been more true than it is now. And we need to keep hope kindled in our hearts, even when the world seems hopeless, especially when the world seems hopeless.

The Hasidic master Reb Nachman (b. 1772) struggled with depression. And yet he taught that despair is a sin. Because despair means the complete absence of hope. And that means we’ve given up on each other, and on ourselves, and on God. And if we’ve given up, we won’t work to repair what’s broken.

That’s another thing it means to me to be a Jew: tikkun olam, repairing our broken world. We are God’s hands in the world. It’s aleinu, it’s on us, to build a world of greater justice and love and hope — and not to give up.

This is the d’varling Rabbi Rachel offered at CBI on Shabbat Chanukah (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)

This week’s Torah portion, Vayishlach, contains the story from which our people takes its name.

Jacob is on his way to meet up with his brother Esau for the first time in years. He sends his family away: he is alone on the riverbank. There an angel wrestles with him until dawn, and blesses him with a new name, Israel — “Godwrestler.” We are the people Israel, the people who wrestle with God.

Jacob — Israel — walks away from that encounter with a limp. His hip has been wrenched; Rashi says it’s torn from its joint. I imagine he was never quite the same after his night-time wrestle. Maybe he could feel oncoming damp weather in his aching hip, or in the sciatic nerve that Torah instructs us not to eat.

Our struggles change us. They may leave us limping.

I think we all know something about that now. The last eighteen months have been a struggle. We’ve wrestled with fear and anxiety, and with loneliness. We’ve wrestled with disbelief at outright lies about the pandemic being a hoax, or about vaccines being an instrument of government control.

Many of us are grappling with climate grief, the fear that our planet is already irrevocably changed. Or with political anxiety, wondering whether “red America” and “blue America” can really remain one nation. Or with the reality that the pandemic is now endemic and will not go away. That’s a lot.

Jacob wrestled for one night and was changed.

How will we be changed by the wrestling we’re doing during these pandemic years?

Earlier this fall I had a bout of sciatica, and I went to see my neighborhood bodyworker. She reminded me that when one part of the body hurts, most likely a different part of the body needs work. My lower back ached, so she worked on my hip flexors! Pain often calls us to stretch in the opposite direction.

That’s a physical truth, but it landed metaphysically. When despair ties us in knots, we need to stretch into hope. Remember what we learned from Mariame Kaba at Rosh Hashanah: hope is a discipline. We have to practice it, and stretch it, and lean into it exactly when our pain pulls us the other way.

Torah tells us that Jacob’s sciatic nerve was wounded in his wrestling. And Torah also references his heel; Jacob’s name means heel. When I was getting treatment for my sciatica, my bodyworker picked up my heels and leaned back, pulling on them gently. “I feel like you’re making me taller,” I joked.

She said: that’s because I am. Stress and tension and gravity all conspire to tighten our bodies, but we can lengthen. In fact, every night while we sleep we get taller as we unclench. Just as astronauts get taller when they spend time in zero-gee, away from the literal pressure of earth’s gravitational pull.

When she pulled on my heels, I could feel my whole body getting longer: legs telescoping, spine lengthening. We compartmentalize — imagining that this body part is separate from that one, or that body is separate from mind and heart and soul — but we are integrated beings: everything is connected.

That’s another physical teaching that lands metaphysically. When we tighten up spiritually, that manifests in our bodies. Stress and tension and gravity tighten us, but rest can help us loosen. Shabbat can help us loosen. Giving ourselves a break from the relentless press of news can help us loosen.

So can stretching ourselves toward hope. When the wrestle feels most overwhelming, when we feel most ground-down by everything that’s broken, that’s exactly when we need to stretch our capacity to hope. Our spiritual practices can help us shift, as the Psalmist wrote, from constriction to expansiveness.

Jacob named the place of the wrestle P’ni-El, the Face of God. May we too encounter divine presence in our wrestling. May our wrenched and tight places give us greater compassion for each other and for ourselves. And may we learn, in our times of constriction, to open up and stretch toward possibility.

This is the d’varling that Rabbi Rachel offered at CBI on Shabbat (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.) Shared with gratitude to Emily at Embodywork.

Our Torah stories are the same every year. But as we change and grow, we find new ideas and understandings in the same old stories.

In the verses from Toldot that we just heard, Isaac is old and his eyes have grown dim. He is preparing to die, and he wants to give his firstborn son a special blessing. Esau and Jacob are twins, but Esau was born first. Isaac sends Esau off to hunt, saying, “bring me back some stew and I’ll bless you.”

That’s when Rebecca steps in, instructing Jacob to fetch a couple of goats. She’ll make a stew that he can bring to his father, and that way, he’ll get his father’s blessing. “But Mom,” says Jacob, “Esau is hairy and I’m not. If Dad touches my arm, he’ll see me as a trickster and I’ll get a curse, not a blessing!”

“If he curses you, let the curse be on me,” says Rebecca. “Just do what I told you to do.” So he does, and she covers him with Esau’s clothes and with goat skins so he feels hairy to the touch. He takes the stew to his dad. He claims to be Esau. He gets his father’s special firstborn-oriented deathbed blessing.

When Esau gets home, he’s furious. He begs his father for a blessing, and the blessing he gets is not a very happy one. Esau starts muttering about how he’s going to kill Jacob as soon as their dad dies. Rebecca tells Jacob to flee, and that’s what sends him off on his big life’s journey.

In previous years, reading this story, I’ve thought about how in the ancient world the older son was always supposed to inherit. Yet throughout Genesis, it’s the younger son who gets lifted up. Maybe Torah’s teaching us that status, or birth order, doesn’t determine our fate.

I’ve thought about how Jacob, whose name means “Heel” because he emerged from the womb clutching Esau’s heel, is kind of being a heel here. It feels like poetic justice when his uncle Laban tricks him into marrying the wrong sister. Maybe Torah’s teaching us that the karma of our choices stays with us.

This year, all I can think is: Rebecca in this story is really not teaching the kind of moral lesson that I wish for. It looks like she wants to make sure her favorite kid gets the blessing, so she tells him to trick his father by pretending to be someone he’s not? I don’t feel good about that.

Earlier in the story, when pregnant, Rebecca asks God why it feels like there’s warfare in her womb. God tells her that two nations struggle inside her, and that the older will serve the younger. Maybe that’s why midrash teaches that she was a prophet: she knew that Jacob had a special destiny.

Maybe she was practicing what would later be called consequentialism: as long as the outcome is good, then the act that produced that outcome must be moral, right? If it gets us to “Jacob becomes the ancestor of the Jewish people,” then whatever steps she took to get there must be okay?

I disagree. How we work toward our goals matters at least as much as whatever those goals are. Integrity matters. Truth matters. Facts matter. I would never instruct my child to pretend to be someone he’s not, even if there were some kind of reward for that pretending.

And generally speaking, Jewish tradition takes integrity really seriously. Rambam teaches that we should never “be one thing in mouth and another in heart,” that our insides should match our outsides, that deceiving another human being is like stealing their mind and we should never do it.

So why are most of our sages okay with what Rebecca did here? Most of the sages of Jewish tradition argue that this wasn’t really a deception, because our mystics teach that Jacob’s soul was formed first in the womb. His essence was special. They see Rebecca as helping Jacob become who he truly is.

My friend R. Mike Moskowitz compares it to someone coming out and changing their clothing style. When Jacob changes his outward appearance, with Esau’s borrowed clothes and the goat skins on his arms, now his dad is finally able to experience him as he’s always seen himself, as he truly is.

I like that interpretation. I agree that parents need to see our kids as they truly are! But for me, it’s a stretch to read these verses that way. If we choose to do that, I think we need to be honest with ourselves that we’re doing a lot of work to make Rebecca’s actions okay when on the surface, they just aren’t.

Maybe what Torah is teaching us here is that even our patriarchs and matriarchs were human just like us, and they made mistakes, just like us.

Because even if you want to argue that only the outcomes matter — the choice that Rebecca makes harms Esau, at minimum. And I think we can make a case that this choice harms Jacob and Isaac’s relationship, too. Even if her intentions were good, Rebecca’s choice has negative impacts on the entire family.

(Just wait until you see how Jacob’s kids treat each other. Let’s just say the unfortunate tradition of parental favoritism doesn’t stop here, and the next generation is a little bit of a mess as a result. Maybe you remember a kid named Joseph, whose brothers hate him so much they sell him into slavery…)

I wish that Rebecca had been able to say to Jacob: don’t worry about your brother, just go be real with your dad. Tell him you love him, and ask him for the blessing you most need. Ask him for the blessing you’re going to need after he dies. Ask him for the blessing that will help you set off on life’s journey.

And as for me, I bless you to be continually growing and changing, to wrestle with our traditions and with God, and to always act with integrity as you live into the wholeness of who you are. I wish that Rebecca had been able to say something like that to Jacob. But at least I can say it now to you.

This is Rabbi Rachel’s d’varling from Shabbat morning services at CBI (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)