The prayer Unetaneh Tokef, which we recite on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, probably dates back to the Crusades, when Christian soldiers en route to the Holy Land slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Jews. We don’t actually have exact data on the number of Jewish deaths at Crusader hands, though in 1298 up to 100,000 Jews were killed by German Rintfleish knights – and that wasn’t a Crusade, just blood libel! Those centuries were not an easy time to be Jewish.

In maybe its most memorable passage, the prayer imagines that on Rosh Hashanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, what our fate in the coming year will be. Who will die by fire and who by flood, who by sword and who by beast. Who will be tranquil, and who will be driven; who will fall down and who will be lifted up.

This year, I’m experiencing that prayer through the lens of Kate Bowler’s memoir No Cure for Being Human, which I read this summer, and which opens with her diagnosis with stage IV colon cancer. Bowler writes:

This year, I’m experiencing that prayer through the lens of Kate Bowler’s memoir No Cure for Being Human, which I read this summer, and which opens with her diagnosis with stage IV colon cancer. Bowler writes:

While I believe that there may be rich meaning at every crossroad in our lives – each meeting and departure, car accident or choice encounter – I do not believe that God will provide for every need or prevent every sorrow. From my hospital room, I see no master plan to bring me to a higher level, guarantee my growth, or use my cancer to teach me. Good or bad, I will not get what I deserve. Nothing will exempt me from the pain of being human.

There may be meaning at every crossroad, but that’s different from claiming that “things happen for a reason.”

I appreciate Bowler’s point that sometimes terrible things just… happen. We may learn valuable things in our suffering. And we may make meaning from and in our suffering – I hope that we do. But that doesn’t mean the suffering is “good” or that the learning feels “worth it.” I admire Kate Bowler’s willingness to say: from my hospital bed I don’t see a master plan.

I don’t understand the Unetaneh Tokef prayer as fatalistic, an angry God making threats about how we’re going to suffer. The prayer says, “At Rosh Hashanah it is written, and at Yom Kippur it is sealed,” but that metaphor doesn’t have to mean that God is predetermining anything. Our tradition regards this time of year as spiritually elastic and malleable. We take a spiritual accounting of who we’ve been and who we want to be. We recognize and confess our screw-ups; we resolve to be better. What’s changeable at this time of year is us.

Yom Kippur is a day for confronting our mortality: not for the sake of wallowing, but for the sake of recognizing that time is short. As Bowler writes, “The terrible gift of a terrible illness is that it has, in fact, taught me to live in the moment. Nothing but this day matters: the warmth of this crib, the sound of [my toddler’s] hysterical giggling…time is not an arrow anymore, and heaven is not tomorrow. It’s here, for a second, when I could drown in the beauty of what I have but also what may never be.”

Living in the moment is not easy. Most of us spend a lot of time in the past, remembering old injuries or old joys, depending on our temperament. And most of us spend a lot of time in the future, looking forward to or dreading whatever we think is to come. But yesterday is over and tomorrow isn’t guaranteed. It’s true for all of us, terminal diagnosis or not. Our job is to remember that, and to open to the beauty in it.

This was brought home for me also in reading R. Julia Watts Belser’s Loving Our Own Bones: Disability Wisdom and the Spiritual Subversiveness of Knowing Ourselves Whole. R. Watts Belser writes:

This was brought home for me also in reading R. Julia Watts Belser’s Loving Our Own Bones: Disability Wisdom and the Spiritual Subversiveness of Knowing Ourselves Whole. R. Watts Belser writes:

We often treat disability as an aberration or imagine it as exceptional. But that’s a strange way of thinking. Disability is a ubiquitous part of human experience, an ordinary part of our existence. The particulars differ for all of us. But the fact that disability will enter our lives? That it will change us and our loved ones? It is a universal truth, a truth that is as inevitable as our mortality.

I remember, from my mother’s long illness, how she didn’t want to talk about her body’s losses. Even when the drugs prescribed for the resistant infection in her lungs gave her neuropathy and hearing loss. I think she wanted to just pretend everything was “normal” for as long as she could. I wonder now how that could have been different – for her and for us – if we’d been able to see her illness not as apart-from normal, but as a part of normal.

Watts Belser writes, “When I use the word disability in this book, I include physical and sensory disabilities, cognitive and intellectual disabilities, mental health disabilities, and long-term health conditions like chronic pain and chronic fatigue.”

Her list drew me up short, in part because it feels so expansive. If we consider all of the things she lists, she’s talking about almost all of us. I think this is part of her point. In the words of disability activist Rosemarie Garland-Thompson, “Our modern culture tells us that disability is an exception when in fact it is the rule of the human life… all of us will become disabled if we live long enough.”

Who by fire and who by water, and who by just… living long enough. We may not know who’s going to suffer by this, and who’s going to suffer by that – but we know that suffering is a radical equalizer, part of being human.

But wait. It’s part of being human, but it’s not the whole story. And disability isn’t necessarily suffering.

Here comes the turn in the prayer, the place where – for me – it pivots toward hope. “Teshuvah, tefilah, and tzedakah have the power to sweeten the decree.” Teshuvah: repentance, return, turning our lives around. Tefilah: spiritual practice. And tzedakah, giving to others in a justice-oriented way. These may not change the material circumstances of our lives (although they might!) But they can change how we experience those circumstances. And that makes me think of what R. Watts Belser writes about the spiritual subversiveness of seeing oneself whole.

Here comes the turn in the prayer, the place where – for me – it pivots toward hope. “Teshuvah, tefilah, and tzedakah have the power to sweeten the decree.” Teshuvah: repentance, return, turning our lives around. Tefilah: spiritual practice. And tzedakah, giving to others in a justice-oriented way. These may not change the material circumstances of our lives (although they might!) But they can change how we experience those circumstances. And that makes me think of what R. Watts Belser writes about the spiritual subversiveness of seeing oneself whole.

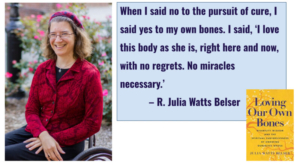

Watts Belser writes: “I could have stayed forever in the land of wanting. Instead, I built a fierce and tender bedrock of radical self-love. When I said no to the pursuit of cure, I said yes to my own bones. I said, ‘I love this body as she is, right here and now, with no regrets. No miracles necessary.’”

Watts Belser writes: “I could have stayed forever in the land of wanting. Instead, I built a fierce and tender bedrock of radical self-love. When I said no to the pursuit of cure, I said yes to my own bones. I said, ‘I love this body as she is, right here and now, with no regrets. No miracles necessary.’”

That is some powerful teshuvah to make with one’s body. Every year when we write down the mis-steps for which we seek forgiveness, someone always writes, “I wasn’t good to my body.” “I didn’t appreciate my body.” “I didn’t treat my body well.” I can relate. As I approach fifty I carry the scars of two strokes and a heart attack. And stretch marks. And some things that don’t work as well as they used to. Not to mention a lifetime of being taught in subtle and pervasive ways that a woman’s body is only worthwhile if it looks a certain way and does certain things. Can I say, “I love this body as she is, right here and now, with no regrets. No miracles necessary”?

When I say “teshuvah, tefilah, and tzedakah,” I wonder whether anyone feels like I’m asking something unreasonable. Am I asking each of us to change our life, become super-religious, and give away everything we have? Not those last two. (Changing our life: yeah, actually. That’s kind of what this season is for.)

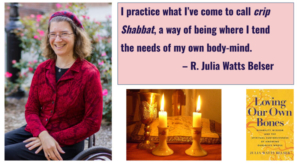

But spiritual practice doesn’t have to look any particular way. One of the most moving passages in the book, for me, is when R. Watts Belser is describing how disability impacts what Shabbat means in her life. She writes:

But spiritual practice doesn’t have to look any particular way. One of the most moving passages in the book, for me, is when R. Watts Belser is describing how disability impacts what Shabbat means in her life. She writes:

I practice what I’ve come to call crip Shabbat, a way of being where I tend the needs of my own body-mind. Sometimes that means letting go of expectation, letting go of ought and should. I recall with vivid clarity the Friday night when all I did was pop a frozen pizza in the oven, or the Shabbos days I’ve lain in bed. I recall the services I’ve skipped, when a week of work snapped back upon my bones, inexorable. When exhaustion swallowed me, when all those body needs I held at bay came home to roost, when rest was not a choice but a demand.

I love the way she writes about attunement to the needs of her own body-mind. Letting go of “should,” and allowing herself to be as she actually is. How profoundly counter-cultural to actually give her body-mind what it needs. How many of us feel we have to apologize for doing that, if we ever even manage to do it at all?

Spiritual practice can be thanking God silently for that frozen pizza, and giving ourselves permission to rest. Or it can be all kinds of other things. It’s not one-size-fits-all: not for all of us in this room, not even for any one of us at every time. Spiritual practice asks us to be real, and to listen to what R. Watts Belser calls our “body-mind,” the integrated whole of who we are.

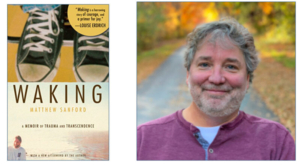

Watts Belser rejects the dualism that would depict us as “a brain in a jar.” I’ve never read a better unpacking of that metaphor – and the damage it can do – than Matthew Sanford’s memoir Waking: A Memoir of Trauma and Transcendence.

Watts Belser rejects the dualism that would depict us as “a brain in a jar.” I’ve never read a better unpacking of that metaphor – and the damage it can do – than Matthew Sanford’s memoir Waking: A Memoir of Trauma and Transcendence.

The book begins with the car accident at thirteen that changed his life. On the way home from a Thanksgiving meal, the family ran off the road on a patch of black ice.

His father and sister were killed. His mother and brother were lightly injured, but basically walked away fine. Matthew broke his spine in several places, along with both arms and several other significant injuries. To this day he is paraplegic, paralyzed from the chest down. His memoir traces the long slow path of recovery.

Talk about “who by fire and who by water.” This is the kind of senseless, out-of-nowhere life-changing event that I imagine the Crusades to have been for the people who lived through that moment in time. One minute everything is familiar, the next minute life is forever changed.

Sanford writes, “What I have actually lost in my experience of myself is an inward connection to much of my body. Below my chest has become a mental dead end – my mind has been blocked from entering. The loss of basic life skills, including my ability to walk, is simply a symptom of this mind-body dislocation.”

He describes, during his recovery, beginning to feel as though he might faintly be able to sense some kind of connection with his feet. The doctors, not wanting him to suffer false hope of walking again, stress that medically there is no way he can “connect” with his paralyzed lower half. The spine is broken. The connection is gone. End of story. At thirteen, he believes them; who among us wouldn’t? So he stops trying.

“Healing is still possible for my mind-body relationship,” he writes later, “and it doesn’t mean that I will walk again. Unfortunately, I do not fully grasp this until I begin to practice yoga many years later.” Did I forget to mention…? Matthew Sanford is now a yoga teacher, who teaches both disabled and “able-bodied” students.

“Healing is still possible for my mind-body relationship,” he writes later, “and it doesn’t mean that I will walk again. Unfortunately, I do not fully grasp this until I begin to practice yoga many years later.” Did I forget to mention…? Matthew Sanford is now a yoga teacher, who teaches both disabled and “able-bodied” students.

The gift I find in Unetaneh Tokef is its recognition that a life-altering paradigm shift could come at any moment. We can’t control that. But we have agency in how we respond. And how we respond can help us build resilience, and even seek joy.

Sanford writes beautifully about what he describes as “silence:”

Silence is what remains when mind becomes separated from body… the medical model’s answer is that I won’t interact with [the silence] at all. … The relevance of this book turns on a simple thought. My traumatic experience of a spinal cord injury and its resulting paralysis has made more tangible a silence that exists in everyone’s consciousness, a silence that can be experienced in the gap between mind and body.

Severing his spine is a profound silencing. His brain can’t reach his feet anymore; his feet can’t send signals back to his brain. At least, not in any way that medicine can understand. But in his mid-twenties he finds a yoga teacher who begins to work with what his body can do, and he develops an intuitive understanding of what yoga poses do energetically and how to engage in them even given his body’s silence.

“We are all leaving our bodies — this is the inevitable arc of living,” he writes. “Death cannot be avoided; neither can the inward silence that comes with the aging process.” He was thrust into that silence at thirteen when he shattered his spine, but all of us will feel that silence if we live long enough. Ultimately, that’s the wisdom in his book that left me feeling most changed. He writes, “As a paraplegic, I can no longer rely on the normal course of my daily life to ensure a healthy connection between my mind and my body. The same is true for all of us.”

But we can build connection between mind and body. If Matthew Sanford can build that connection when he’s paralyzed from the chest down, that tells me that I can, too – we all can. First we may need to recognize that the mind-body connection is there, even if we’re not accustomed to listening through it. (My name for what connects mind and body is soul. You don’t need to call it that, if you don’t want to.) Maybe in order to listen through that conduit we need to figure out how to love our imperfect bodies as they are. And maybe it helps us if we can learn to live in the moment and recognize the beauty of now, even if now isn’t everything we wish for.

In Kate Bowler’s cancer memoir, she writes, “God, let me see things clearly. I must accept the world as it is, or break against the truth of it: my life is made of paper walls. And so is everyone else’s.”

In Kate Bowler’s cancer memoir, she writes, “God, let me see things clearly. I must accept the world as it is, or break against the truth of it: my life is made of paper walls. And so is everyone else’s.”

Who by fire, and who by water; who will be restless, and who will be at peace; who will be humbled, and who will be exalted – we can’t know. But making a practice of teshuvah, tefilah and tzedakah will change how we experience whatever comes. Teshuvah, tefilah, and tzedakah are all resilience-builders. They help us bend, rather than breaking. And that’s one of Judaism’s greatest spiritual gifts. It might be the reason we’re still here after 3,000 years that haven’t always been great times to be a Jew. (That sense of a “we” that’s still here even after any one of us is gone – that’s resilience, too.)

“My life is made of paper walls,” writes Bowler. Even without a diagnosis or a catastrophic injury, our capacity is limited and our time is short. Most of us turn away from these truths most of the time. Yom Kippur comes to remind us to do otherwise. To live in the moment, and make teshuvah now. That’s a practice.

Yom Kippur calls us into spiritual life, including sitting with silence. What if we could, like Matt Sanford, learn to listen to the silence within our body-minds with compassion? That’s a practice. And Yom Kippur calls us to tzedakah: to giving what we can to others in need, as part of our pursuit of tzedek, justice. That’s a practice, too.

God opens the Book of Memory, but we’re the ones who write it. We can’t control the possibility of fire or flood, sword or wild beast, black ice on the highway or genetic predisposition. But we get to write the book of what we do with the life we’ve got.

And when we truly inhabit this moment, right here, like Kate Bowler – when we honor our actual bodies and their limitations with love, like R. Julia Watts Belser celebrating “crip Shabbat” or rejoicing in her wheels – when we listen into the body’s silence, like Matthew Sanford, and learn how to hear our inherent connectedness – we build the resiliency that allows us to live in joy. Not despite what’s broken in our lives or in our world, but in tandem with it. Grief can coexist with joy, as bitter can coexist with sweet. We just have to make a practice (there’s that word again) of letting the joy in.

Our choir invites us now, in the words of poet Mark Nepo and music by our own Adam Green, to “grow by simply listening.” As we prepare for Yizkor, I invite us also to listen into the silences left by those who are no longer with us in this life… and listen into what we might need to say to our dead during silent memorial prayer.

This is the sermon that Rabbi Rachel offered at Yom Kippur Morning Service; cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.