This week’s Torah potion, Vayechi — “He lived” — is bookended with a pair of deaths. We begin with Jacob. He offers blessings and curses to his children and grandchildren. He makes Joseph promise to bury him in the Cave of Machpelah where his ancestors are buried. And then his life ends.

By the end of the Torah portion, it’s Joseph’s turn. He tells his family that someday, when God lifts us out of Egypt, he wants his bones to be carried out of there too. As Joseph’s story ends, so does Genesis. Joseph is the last patriarch whose story we experience as part of our spiritual family tree.

When our story begins again in Exodus, a lot of time has passed. In Exodus we’ll enter the story of a community rather than a family. The first time I studied the parsha this week, I thought about burying my own father. And then I expanded my view, and I noticed something that feels important.

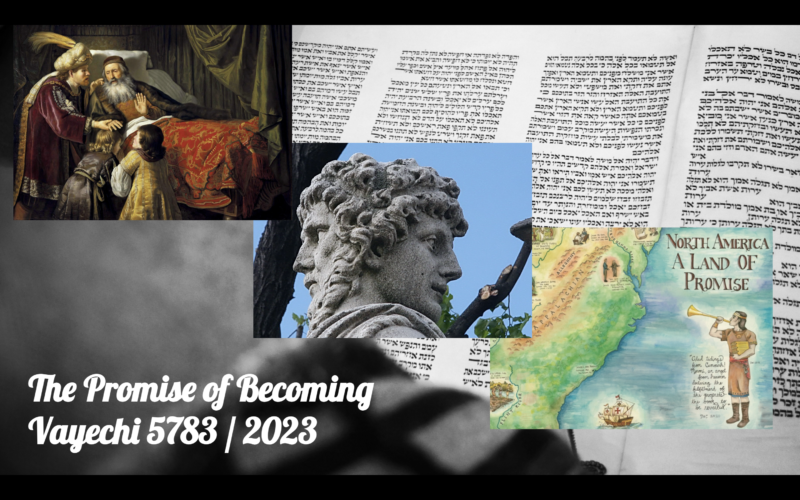

There’s a difference in the two death scenes that feels relevant to me. Jacob says “bury me with my ancestors.” He didn’t live in Egypt for long, and what he wants after death is to go back to where he was before, where his generations are buried. In a sense, he reaches backward.

Joseph says, “God will take notice of you and bring you up to the Land of Promise,” so take me with you when you go. Geographically, he’s talking about the same place, so if this is a physical descriptor, there’s no difference. But notice: Jacob references the past. Joseph invokes the future.

Joseph is saying: I know that God is going to call you into something new. My life brought me to places my ancestors couldn’t have imagined, and your lives will go places I couldn’t have imagined, and that’s as it should be. Grow, change, mature into freedom! Just bring part of me with you when you go.

Two fundamentally different approaches. Take me back to where I was before, or what my ancestors did before, or what I’ve been told my ancestors did… or take me forward into change, into becoming. Becoming can be scary; it may ask a lot of us. But turning back won’t get us where we need to be.

The idea of the land of promise can mean a lot of things: a physical place, a spiritual space, a future redemption. In 1630, John Cotton called America a land of promise. In 1785, so did George Washington. In the 20th century, countless immigrants (many of them Jewish) sought promise here.

There are deep tensions between that idea and the worldview of Native American nations who lived in mutual care with this land and its abundance before we got here. For me the idea of a land of promise is most resonant when it’s not about geography or ownership, but about ideals and aspirations.

And this turns out to be a poignant week to be contemplating our national ideals and aspirations — between the dysfunction on view in Congress and the anniversary of the January 6 attack on the Capitol. (Relatedly, all but two of those who have been holding Congress hostage are election deniers.)

We have a long way to go to live up to democracy’s promise. The equity and inclusion inherent in the declaration that “all… are created equal.” The integrity shining in the ideal of “liberty and justice for all.” Yes: that’s the world I want! I think of these ideals as more as a direction than a destination.

Will we ever “get there” — to perfect democracy; to perfect justice; to a world where (in the words we often sing as our Aleinu) “everywhere will be called Eden once again”? Probably not. But our spiritual covenant as Jews — and, I think, as Americans — calls us to keep pushing in that direction.

I keep returning to the image of Jacob on his deathbed looking back, and Joseph on his deathbed looking forward. I think this moment calls us to emulate Joseph, and to recognize that our yearned-for future of justice and integrity may ask a spiritual expansiveness our ancestors never imagined.

Joseph knew that God would call his descendants, and their descendants, into something new he couldn’t foresee. (As our story goes: from servitude to holy service, from slaves with no autonomy to whole souls in willing covenant with the Holy. Tune in next week as we begin the Exodus story.)

We can’t know where our story will go — our personal story, our family story, our national story. But we can dream of promises fulfilled, and then build toward that future. We can do everything we can to aim ourselves and our communities toward integrity and justice, human dignity and hope.

That’s my prayer for us this week:

May we be like Joseph!

May our every descent be for the sake of ascending higher.

And may we embrace becoming all that we can become.

This is the d’varling that Rabbi Rachel offered on Shabbat morning (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)