Earlier this summer I started asking, “what do you want to hear a rabbi speak about at the high holidays?” I got a lot of really powerful answers. One of your answers – actually a question – lodged in my heart: “How can we pray to a God who appears not to be listening? To whom are we praying, and for what?”

The question wouldn’t let me go. So I sat down to answer it, and I wrote pages about how our ancestors answered this question. And then I stopped myself. The question wasn’t, “how did our ancestors pray in their era.” It’s how can we pray in ours. It can feel like God isn’t listening, maybe like God isn’t even there. I mean, God hasn’t fixed anything, so what are we even doing? Who are we talking to, and why?

Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks, the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, wrote about a visit to Auschwitz where he saw countless photographs of small children who were killed. He broke down and wept and asked, “God, where were You?”

Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks, the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, wrote about a visit to Auschwitz where he saw countless photographs of small children who were killed. He broke down and wept and asked, “God, where were You?”

And words came into my mind. I’m not claiming they were any kind of revelation, but this is what they said: “I was in the words, ‘You shall not murder.’ I was in the words, ‘You shall not oppress a stranger’. I was in the words that were said to Cain when he killed Abel. ‘Your brother’s blood is crying to Me from the ground.’”

And suddenly I knew that when God speaks and human beings refuse to listen, even God is helpless in that situation…

When we refuse to listen, even God is helpless. This feels very modern to me, though in some ways it’s a very old idea: tradition teaches that everything is in God’s hands except our awe of God. (Brachot 33b) In other words, the one thing God can’t control is whether we live with awe and choose to do what’s right.

Our tradition teaches, “Wherever Israel was exiled, the Indwelling Presence went with them.” (J.T. Avodah Zara 1:17) The word rendered here as “Indwelling Presence” is Shekhinah – God within and among us. When we are in exile, part of God is too. Maybe here in this broken world we can pray to the face of God that is here with us in the brokenness. This feels to me like pastoral care: God is the hospital chaplain sitting by our bedside. (Or sometimes I imagine it the other way around: maybe our presence comforts God.)

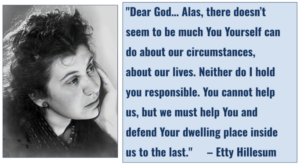

R. Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, the rabbi of the Warsaw Ghetto, taught that when we suffer, God’s very Name becomes occluded; God suffers with us. (Rosh Hashanah 1941) But he doesn’t explain why God doesn’t “reach in” to fix things. Etty Hillesum, murdered in Auschwitz at 29, had her own take on that:

R. Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, the rabbi of the Warsaw Ghetto, taught that when we suffer, God’s very Name becomes occluded; God suffers with us. (Rosh Hashanah 1941) But he doesn’t explain why God doesn’t “reach in” to fix things. Etty Hillesum, murdered in Auschwitz at 29, had her own take on that:

“Dear God… One thing is becoming increasingly clear to me: that You cannot help us, that we must help You to help ourselves. And that is all we can manage these days and also all that really matters: that we safeguard that little piece of You, God, in ourselves. And perhaps in others as well. Alas, there doesn’t seem to be much You Yourself can do about our circumstances, about our lives. Neither do I hold you responsible. You cannot help us, but we must help You and defend Your dwelling place inside us to the last.”

Etty talks about what the Hasidic masters called the God-spark within, the spark of something ineffable that makes us alive. God “far above” doesn’t seem to reach in and change things anymore, but God “deep within” is precious and needs our care.

But why would we pray to a God Who doesn’t seem to fix things? My friend and teacher Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg wites, in her essay Permission Slip:

But why would we pray to a God Who doesn’t seem to fix things? My friend and teacher Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg wites, in her essay Permission Slip:

There is no version of any understanding of the divine that I have that involves me praying for a pony and getting a pony. Or a fast car or that gig that I want or a parking spot or whatever.

Courage, patience, compassion? That’s different. Those are inside you. When you pray for those, you are actually summoning great, gorgeous sleeping aspects of yourself from the deep, inviting them to rise to where you can see them, find them. You’re asking the divine to be your partner in finding them, asking for the capacity to access what is already available to you.

In this understanding, God is the force that enables us to access our highest and best selves. With God’s help we can be better than we thought we could be.

We pray in order to remind ourselves to make a better world real. We sang earlier about how we are guided by hands that uplift us, we are urged-on by eyes that meet us, we are counseled by voices that guide us – and “ours are the arms, the fingers, the voices.” We are God’s instruments in the world. We pray for justice to remind to pursue justice. We pray for peace to remind ourselves to make peace.

Our usual Hebrew word for prayer is תפילה, from להתפלל – a reflexive verb that means to judge oneself or discern oneself. When we engage in tefilah, we’re looking inside. We’re discerning who we are and who we want to be. Our traditional liturgy for today is rich with the metaphor of God-as-judge, but embedded in this Hebrew word is the idea that every time we pray, we are judging ourselves. Not in a punitive way, rather in an introspective way.

Our usual Hebrew word for prayer is תפילה, from להתפלל – a reflexive verb that means to judge oneself or discern oneself. When we engage in tefilah, we’re looking inside. We’re discerning who we are and who we want to be. Our traditional liturgy for today is rich with the metaphor of God-as-judge, but embedded in this Hebrew word is the idea that every time we pray, we are judging ourselves. Not in a punitive way, rather in an introspective way.

Prayer is a spiritual tool for introspection. With our fixed liturgy we return to the same words day after day, year after year, but we are always changing. How do the familiar words land with me now? What is arising in me when I say them?

What do I feel, and what do I resist feeling? “The function of prayer is not to influence God, but rather to change the nature of the one who prays.” That’s 19th-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, though it feels Jewish to me.

What do I feel, and what do I resist feeling? “The function of prayer is not to influence God, but rather to change the nature of the one who prays.” That’s 19th-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, though it feels Jewish to me.

We also learn things about ourselves during personal or spontaneous prayer. Remember the story of Chanah from the first day of Rosh Hashanah? She desperately wanted a child, so she went to a sacred place and she poured out her yearnings. Chanah teaches us that another fundamental aspect of prayer is speaking what’s on our heart.

What’s on our hearts this year might be grief, or anxiety, or rage, or helplessness. I am here to tell you that whatever it is we are feeling, no matter how vast or overwhelming our feelings might be, God (as I understand Them) can take it. And whatever it is, we need to express it, because stifled feelings can fester. Hey, good news, friends: Yom Kippur lasts for 25 hours. And our tradition teaches that right now, the Gates of Heaven are open. Operators are standing by. God is waiting for our call.

Are the Gates really more open today than at any other time? I mean, our tradition also says (Zohar 3:31b) the Gates might stay open until Shemini Atzeret – that’s the 8th day of Sukkot, so 12 days from now. And there’s another tradition (Zohar 1:220b) that says the Gates might stay open through Chanukah if we really need them. And there’s another tradition that says that the Gate of Tears is always open, so if we call out with a broken heart, the call always “goes through.”

Are the Gates really more open today than at any other time? I mean, our tradition also says (Zohar 3:31b) the Gates might stay open until Shemini Atzeret – that’s the 8th day of Sukkot, so 12 days from now. And there’s another tradition (Zohar 1:220b) that says the Gates might stay open through Chanukah if we really need them. And there’s another tradition that says that the Gate of Tears is always open, so if we call out with a broken heart, the call always “goes through.”

I love the expansiveness of these teachings, the reminder that it’s never too late. I hold them in balance with the injunction to “make teshuvah one day before our death.” (Pirkei Avot 2:10) I offered that teaching one recent Monday during tefilah / prayer time at Jewish Journeys. Immediately a kid’s hand shot up into the air. “But how do you know when that’s going to be?” Of course, we don’t.

The time for teshuvah is always now. And if there’s something we need to say to God, there’s no time like the present. As always, if the word “God” doesn’t work for you, find one that does. Meaning. Justice. Love. The Universe. Ultimate reality. That spark within us that makes us part of something greater than ourselves.

When God’s face seems hidden from us, I don’t believe that God is gone or isn’t listening. In my understanding God is like the moon. Sometimes the moon is full. Sometimes the moon is invisible. But the moon is there, even when we can’t see her light. God is there, even when we can’t feel Their presence. Martin Buber wrote that during the Shoah, it was as if we were living through “an eclipse of God” – a time when God’s face was hidden from us. Many of us have felt that way over the last year.

When God’s face seems hidden from us, I don’t believe that God is gone or isn’t listening. In my understanding God is like the moon. Sometimes the moon is full. Sometimes the moon is invisible. But the moon is there, even when we can’t see her light. God is there, even when we can’t feel Their presence. Martin Buber wrote that during the Shoah, it was as if we were living through “an eclipse of God” – a time when God’s face was hidden from us. Many of us have felt that way over the last year.

This is a feeling as old as the psalms, maybe as much as 3000 years old. In Psalm 27 (the psalm for Elul and the Days of Awe) we find the plea, אַל־תַּסְתֵּ֬ר פָּנֶ֨יךָ / “Do not hide Your face from me!” Sometimes God’s face can feel hidden in a big way, a communal way: during times of crisis or war. Sometimes God’s face may feel hidden in a small and personal way – like, “no one else may be feeling this, but I am.”

There have been times in my life when God has felt absent. Sometimes my spiritual practices help me reopen that felt sense of connection… and sometimes, when I’m really struggling with depression or grief, my spiritual practices can feel hollow. I’ve learned, in those times, to pray for the ability to feel my own prayers again.

What keeps us from feeling God’s presence? Our busy-ness. Our to-do lists. The ready availability of ways to numb ourselves to feeling, whether through television or social media or doomscrolling or eating and drinking (or avoiding eating and drinking). Our ambivalence. Our trauma. Our depression and anxiety. Our discomfort with the things we might discover if we sit in the stillness and let ourselves feel. Maybe we don’t want to cry. Maybe we don’t want to get angry. Maybe we don’t want to open ourselves to the possibility of hope or joy because what if we can’t find them? There are a million ways and a million reasons to close ourselves off.

Authentic spiritual practice asks us to open ourselves up, and so does this sacred day.

Authentic spiritual practice asks us to open ourselves up, and so does this sacred day.

One of my favorite ways to open up is talking aloud to God when I’m driving alone in my car. Following in the footsteps of my teacher Reb Zalman z”l, I imagine the Shekhinah – the face of God that we can relate to; God in creation, God with and within us – sitting in my front seat. In my imagination, she’s resting her feet on the glovebox and she’s wearing sandals with a purple pedicure. As I drive, God listens with infinite kindness as I unburden my heart.

But you don’t have to share my “belief in” God – my feeling that there is Something or Someone out there listening with tenderness. The practice of crying out can make a difference in us, whether or not we think there’s a Listener.

The medieval Jewish philosopher Rambam says that the first step of teshuvah is to make vidui aloud, to “confess” verbally where we’ve gone wrong. (We do a lot of that on Yom Kippur.) Centuries later, the Hasidic master Reb Nachman prescribed a practice of hitbodedut, speaking aloud to God in the forest. Both of them knew that hearing ourselves say things can change us. And Yom Kippur is, at least in small part, about the proposition that we need to change, that our world needs to change.

Even if we don’t “believe in God,” we can still do hitbodedut. We can still pray our liturgy. We can even engage in the petitionary prayer of the heart. I’m not all that concerned with belief. I’m more interested in us experiencing the sacred. And even as central as my experience of God is for me, that’s not required, either.

As these 25 hours of Yom Kippur sweep across the globe [here’s an amazing tiny timelapse!], Jews everywhere are looking within and pouring out what’s on our hearts. There is something powerful about doing this inner work in community, knowing that others are doing it now too.

As these 25 hours of Yom Kippur sweep across the globe [here’s an amazing tiny timelapse!], Jews everywhere are looking within and pouring out what’s on our hearts. There is something powerful about doing this inner work in community, knowing that others are doing it now too.

In services tonight and tomorrow, pay attention to what bubbles up. What resonates? What feels uncomfortable? What makes us tune in, and what makes us turn away? So much of our liturgy for today is in the plural. “We confess that we have sinned.” “Forgive us, pardon us, grant us atonement.” What does it feel like to be part of a “we,” an “us”? If I’m not feeling these words for me, can I feel them as part of an “us”?

During the silent amidah, go inside and see what’s on your heart, and pour that out – to God far above or God deep within. Walk our labyrinth tomorrow if the weather’s decent, and spend those long minutes talking to God. I recommend murmuring out loud, like Reb Nachman said to do.

You’re not sure what God is, or you’re not sure what prayer does? That’s fine: what if you do it anyway? What do you have to lose?

The question that came to me was “How can we pray to a God who appears not to be listening?” It is core to my own theology that God* – asterisk: that word is shorthand for so many different ideas and understandings – God is always listening.

Listening, but not “reaching in” to fix. All I can conclude is that the fixing is our job. We pour out our hearts because we need to, because that’s how we learn who we are. And our time spent in prayer isn’t a magic formula that makes the universe do what we want: it’s a spiritual practice that inspires us to build the world that we need.

I promise you that if you spend this day searching your heart for what you need to say, and saying it – to yourself, to God, to the great beyond – it will be a day well-spent. Sometimes prayer has no words, just the cry of the broken heart. Sometimes we pray because we want to change or be changed. Sometimes we might not know why we’re praying, or for what, until we see what words we need to say.

I promise you that if you spend this day searching your heart for what you need to say, and saying it – to yourself, to God, to the great beyond – it will be a day well-spent. Sometimes prayer has no words, just the cry of the broken heart. Sometimes we pray because we want to change or be changed. Sometimes we might not know why we’re praying, or for what, until we see what words we need to say.

My Facebook questioner this summer asked not only how can we pray, and to whom, but also for what. I don’t know what we each pray for in our personal prayers. But I’ve got one last teaching about what we pray for collectively.

Through northern hemisphere fall and winter, starting at Shemini Atzeret, our daily liturgy asks God for rain. In summer months, starting at Pesach, our prayers don’t ask for rain but rather for dew. In the place where our prayers began it simply does not rain in summer. Our sages teach that we don’t pray for the impossible, because doing so might harm our capacity to have faith.

But our liturgy always includes prayers for peace. Our sages ensconced that prayer in our liturgy all year long, which means it must always be possible. Maybe God can’t make rain out of dry skies, but with God’s help we can always seek peace.

In the words of R. Abraham Joshua Heschel, “Prayer cannot bring water to parched fields, or mend a broken bridge, or rebuild a ruined city; but prayer can water an arid soul, mend a broken heart, and rebuild a weakened will.”

In the words of R. Abraham Joshua Heschel, “Prayer cannot bring water to parched fields, or mend a broken bridge, or rebuild a ruined city; but prayer can water an arid soul, mend a broken heart, and rebuild a weakened will.”

May our prayers tonight and tomorrow nourish our souls and awaken our hearts. May our words and our silences help us to know ourselves more fully. May we pour out our hearts before the One Who hears all prayer. And may today help us return to being who the world most deeply needs us to be.

This is the sermon that Rabbi Rachel offered at Kol Nidre (& the song our choir sang afterwards); cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.