Guest Post: “Getting “Unstuck”: Moving from Awareness and Knowledge to Action”

This guest post is from cantorial soloist and CBI member Ziva Larson, who led Shabbat services on Saturday, July 22, 2023.

Have you ever had a time when you felt “stuck”? When you know something intellectually but can’t quite figure out what to do next?

Maybe it’s something like, “I love reading for pleasure, but I never seem to have time for it anymore.” Or, “I want to have a better relationship with my friend / partner / parent / kid / etc.” Or, “My current array of responsibilities and activities feels out of balance and isn’t working for me.” Or even, “The hinges on my front door are constantly squeaking and seriously annoying me!”

The common theme here is that we are aware of something that we would like to change, but we haven’t yet taken action to make those changes.

Of course, it is ultimately up to us to decide whether or not to take steps to implement changes in our lives.

That being said, there usually comes a time when we must move from awareness and knowledge to action in order to improve our lives, promote our wellbeing and that of others, fight for justice, and work to repair the world.

In our parashah this week — Parashat D’varim — which begins the book of Deuteronomy, the fifth and final book of the Torah, Moses says to the Israelites, “Our God יהוה spoke to us at Horeb, saying: You have stayed long enough at this mountain.” (Deut. 1:6).

This statement is clear enough on its own, but the beginning of the next verse (Deut. 1:7) makes it even more forceful. God says “p’nu u-s’u lachem” (פְּנוּ וּסְעוּ לָכֶם), which is literally a direct commandment: “Clear out and travel!” (Or, more colloquially, “Get your butt moving and leave!”) With slightly different Hebrew vowels, you could also read it as: “Turn toward/face [your new destination] and travel!”

Why is this statement important? And why is it so imperative that the Israelites leave Horeb? To understand this, we must first understand the significance of Horeb.

Horeb is another name for Mount Sinai, the place where the whole Israelite community — all adults and children from past, present, and future generations — received a direct communication from God. (Deut. 5:1-4)

In this communication, God gave the Israelites the gift of Torah – the gift of teachings, guidance, instructions, mitzvot (or, sacred ethical, moral, and religious obligations and deeds), customs, and the foundations of Jewish tradition and practice. God also sealed a covenant of belonging and relationship with the whole Jewish community at Mount Sinai. (Ex. 19:5-6)

Furthermore, if we go back to before the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, Horeb is the place where Moses encountered God in a burning bush and received instructions for freeing the Israelites from slavery in Egypt and leading them to the Promised Land.

Given this information, Horeb, or Mount Sinai, can be understood as a metaphorical place of learning, knowledge, understanding, and awareness.

For instance, throughout our lives as we learn and grow as individuals, we are hopefully also gaining awareness and knowledge of the injustice in the world.

However, having awareness and knowledge of injustice is not enough. In the Jewish community, we often hear the phrase “Tzedek, tzedek, tirdof (צֶדֶק צֶדֶק תִּרְדֹּף) — Justice, justice you shall pursue.” (Deut. 16:20) The pursuit of justice is one of our core values as a Jewish people. But we can’t pursue justice without action. As God said to the Israelites in our Torah portion this week, “You have stayed long enough at this mountain. Turn toward your new destination, leave, and travel!” (Deut. 1:6-7) At some point, we must move beyond awareness and knowledge and into action.

But what does that mean? And where do we go after Mount Sinai, after our time of learning and gaining knowledge, understanding, and awareness?

Another verse in this week’s Torah portion provides the beginnings of an answer.

(For context, in Deuteronomy, Moses recounts the Israelites’ story to them before they enter the place known as the Promised Land. He does this in order to remind the Israelites of their history, challenges, responsibilities, and potential as a community.)

Moses says to the Israelites, “We set out from Horeb and traveled the great and terrible wilderness that you saw, along the road to the hill country of the Amorites, as our God יהוה had commanded us. When we reached Kadesh-barnea, I said to you, ‘You have come to the hill country of the Amorites which our God יהוה is giving to us.’” (Deut. 1:19-20)

But where is the hill country of the Amorites? Maybe it’s a specific geographic location. However, we could also understand it as another metaphorical place.

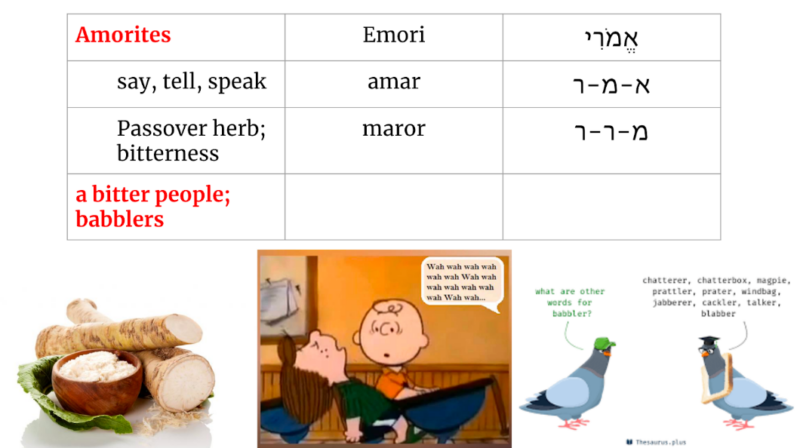

In Hebrew, the name of the people known as the Amorites is “Emori” (אֱמֹרִי). The root of this word is א-מ-ר (amar), meaning “say, tell, speak.” This word is also related to the root מ-ר-ר (maror), which is the bitter herb we consume at Pesach (Passover) as well as the word for the feeling of bitterness. Essentially, then, the meaning of the name “Amorites” is: “a bitter people” and “babblers.”

Therefore, the hill country of the Amorites could be understood as a metaphorical place — or a state of being — in which there exists bitterness and resentment, where words both help spread that bitterness and resentment and are used in place of any action, thereby maintaining the status quo and perpetuating harm.

So if the hill country of the Amorites is the Israelites’ destination, God’s promised land, why are they being given a place of bitterness and empty speech? And how can we reconcile the fact that, if read literally, it sounds like God is displacing the indigenous population so the Israelites can steal the Amorites’ homeland for themselves?

I would argue that this is actually a continuation of our metaphor. If we understand the hill country of the Amorites as any place in which bitterness and empty speech are thriving and perpetuating harm — and perhaps as any community or nation in which we already reside — then perhaps the whole point of our presence in these places is to work to effect change and healing so that each place — each of our communities — can become a Promised Land — a land of promise and hope — for everyone.

However, in order to do this, we need to leave Mount Sinai. We must transition from learning to doing. We can do this by joining forces with marginalized groups, embracing intersectionality, and making space for and amplifying the voices of those who are often overlooked or silenced. We can do this by supporting, promoting, and participating in actions that challenge and dismantle the status quo and systems of injustice and oppression.

Actions speak louder than words. With ACTION we can triumph over those who hide behind speech and words to maintain the status quo of unjust and oppressive systems and practices. With ACTION we can effect change and bring about justice and healing.

Of course, looking at the big picture, this is a monumentally-overwhelming task. However, we can take heart from some words from Mishnah. Rabbi Tarfon, one of our sages, wrote, “It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it.” (Pirkei Avot 2:16)

In other words, although the task in front of us may be hugely overwhelming, we must each do our part to build a Promised Land in our world.

By leaving Mount Sinai – by moving beyond our time of learning and gaining awareness —

by traveling to the hill country of the Amorites – by going the the places full of bitterness and empty speech —

by taking possession of the land promised by God – by taking action to build a promised land of abundance and prosperity, freedom from oppression, physical and spiritual nourishment for all, and completeness and harmony —

then we will truly reach the Promised Land.

Shabbat shalom.

References

- Sefaria:

- Torah:

- Exodus 19:5-6: https://www.sefaria.org/Exodus.19.5-6?lang=bi&aliyot=0

- Deuteronomy 1:6-8 (D’varim): https://www.sefaria.org/Deuteronomy.1.6-8?lang=bi&aliyot=1

- Deuteronomy 1:19-21 (D’varim): https://www.sefaria.org/Deuteronomy.1.19-21?lang=bi&aliyot=1

- Deuteronomy 5:1-4: https://sefaria.org/Deuteronomy.5.1-4?lang=bi&aliyot=0

- Deuteronomy 16:20: https://www.sefaria.org/Deuteronomy.16.20?lang=bi&aliyot=0

- Mishnah:

- Pirkei Avot 2:16: https://www.sefaria.org/Pirkei_Avot.2.16?lang=bi

- Torah:

- Ask a Rabbi: Why is Israel Called the Land of “Milk and Honey”? (Rabbi Julie Zupan, 2015.02.17, JewishBoston): https://www.jewishboston.com/read/ask-a-rabbi-why-is-israel-called-the-land-of-milk-and-honey/

- Land of Milk and Honey – Idiom, Origin & Meaning (Candace Osmond, Grammarist): https://grammarist.com/idiom/land-of-milk-and-honey/

- Jewish Theological Seminary Torah Commentary

- God’s Human Partner (Ismar Schorsch, 2023.01.13): https://www.jtsa.edu/torah/gods-human-partner-2/

- The View From the Other Side (Stephen P. Garfinkel, 2014.08.01): https://www.jtsa.edu/torah/the-view-from-the-other-side/

- My Jewish Learning

- Mass Revelation at Sinai (Rabbi Lawrence Hajioff): https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/mass-revelation-at-sinai/

- What Does “Torah” Mean? (My Jewish Learning): https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/what-does-the-word-torah-mean/