The guest post below is the D’var Torah that CBI member Ziva Larson offered at Shabbat Morning Services on Saturday, August 27, 2022.

Digging into Dietary Laws:

Uncovering Instructions for Ethical & Sustainable Consumption

From Parashat R’eih – Deuteronomy 12:17-25

This week, I want to invite you all on an expedition as we dig into some of the dietary laws we find in our Torah portion for this week. So let’s put on our work boots, grab a shovel (and some sunscreen, if — like me — you need it!) and head over to our excavation site: Parashat R’eih.

In Parashat R’eih, we learn that once the Israelites settle in the Promised Land, they will be permitted to eat meat in their settlements — their home communities, not just at the centralized holy sanctuary. This change carries a special significance that may not be obvious at first glance. First, this change made meat accessible to more people, including those who might be considered ritually “impure” (and who therefore would not be permitted to offer sacrifices at the sanctuary) and those who might live too far from the sanctuary to make regular trips there. Making meat accessible to more people helped to support and sustain the community.

Second, in biblical times, meat was eaten infrequently due to a lack of refrigeration and the fact that living animals provided many other valuable products, such as milk, wool, and offspring. The lack of refrigeration meant that meat had to be consumed immediately. Since most animals provided more meat than a single person or family could consume in one sitting, meat had to be shared with others in the community to prevent it from going to waste. Again, this practice of sharing meat helped both to build community and to support and sustain the community.

Although meat could now be eaten outside the sanctuary, other offerings were still required to be consumed at the sanctuary. Furthermore, the Israelites were explicitly commanded to share their contributions with the Levites, who owned no land and who therefore had less privilege and were unable to support themselves. This commandment can be understood more broadly in the present day as a reminder that we have a duty to support those in our community who are underprivileged.

These dietary laws that promote actions that support and sustain the community and those with less privilege provide a context for another commandment that, at first glance, seems to pertain only to food and is rather baffling. Deuteronomy 12:23 reads:

רַ֣ק חֲזַ֗ק לְבִלְתִּי֙ אֲכֹ֣ל הַדָּ֔ם כִּ֥י הַדָּ֖ם ה֣וּא הַנָּ֑פֶשׁ וְלֹא־תֹאכַ֥ל הַנֶּ֖פֶשׁ עִם־הַבָּשָֽׂר׃

“Rak chazak l’vilti achol ha-dam ki ha-dam hu ha-nafesh v’lo tochal ha-nefesh im ha-basar.”

“[But] be strong to not consume the blood because the blood is the life and you must not consume the life with the meat.”

What does this mean? And why does it matter, anyway? Let’s parse out the meaning first.

We know that meat provides nourishment and strength, but why is blood equivalent to life, and why can’t we consume the life with the meat? If we look at the Hebrew, we can see that the Hebrew word that is translated as “life” is actually “nefesh” (נֶפֶשׁ). We typically understand nefesh as a word for “soul.” In B’reishit Rabbah, a talmudic-era midrash on the book of Genesis (or B’reishit), we learn that there are actually five different words for soul: nefesh (נֶפֶשׁ), ru’ach (רוּחַ), n’shamah (נְשָׁמָה), chayah (חַיָּה), and y’chidah (יְחִידָה). Nefesh is considered the lowest — or the most fundamental — word for soul, the word that really represents the essence of something.

Let’s take a break from our digging and review what we know so far:

- Meat provides us with nourishment and strength, with something we need to survive.

- “Meat” can be a metaphor for anything that we need in order to survive.

- We are not supposed to consume life with meat.

- Nefesh is the soul, or essence, of something — it is life.

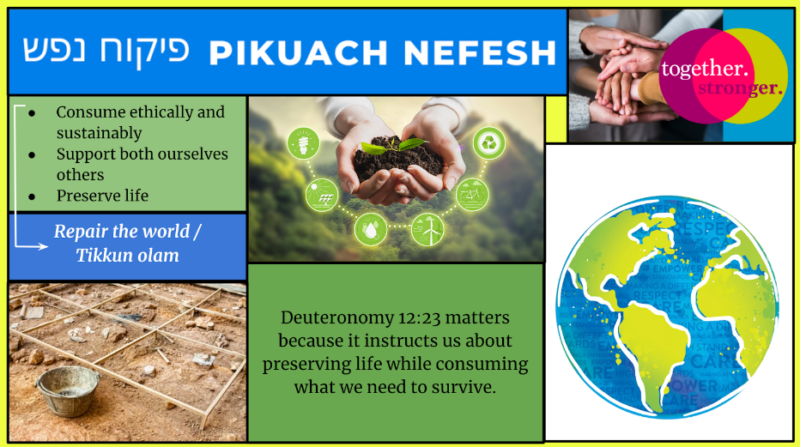

These points help clarify the meaning of Deuteronomy 12:23. Essentially, this verse says: “It is ok to consume what you need to survive, but do not consume or destroy life in the process of consuming what you need to survive.” In other words, this verse is not just about dietary laws. It is telling us to consume ethically and sustainably and to not disregard, exploit, harm, or destroy other people, places, and things in our pursuit of what we need to survive.

We can go even further and look at this verse in the context of the previous verses that emphasized supporting and sustaining the community. In this context, Deuteronomy 12:23 is saying that we, both individually and collectively, are responsible for taking care of, nourishing, and supporting both ourselves and those who are underprivileged, and we are responsible for doing so in an ethical and sustainable way.

But what about the beginning of Deuteronomy 12:23, the part that says to “[…] be strong to not consume [the life with the meat]”? What does that mean? It means that observing this mitzvah requires a special, intentional, mindful effort. It takes strength to refrain from exploiting, damaging, and destroying the life or essence of other people and beings and this planet in our pursuit of nourishment, comfort, privilege, and power.

Of course, we human beings are not always successful at consuming ethically and sustainably. And we all — individually and collectively — experience consequences as a result of our own or others’ disregard for and exploitation, damage, and destruction of other people and beings and the planet — in other words, of life — in the pursuit of self-interests. Our current events provide us with a plethora of examples, of which I will list only a few:

- Climate change and the associated extreme weather events around the world, including the current drought here in Massachusetts.

- Economic inflation.

- Widespread poverty and financial insecurity and lack of adequate housing, food, healthcare, and other social supports.

- Frequent mass shootings.

- Increased health risks and deaths due to attacks on bodily autonomy and freedom of choice.

- Widespread and systemic discrimination against and oppression of BIPOC, trans and nonbinary individuals, queer individuals, women, people with disabilities, and many other marginalized groups of people.

This brings us back to the question of why Deuteronomy 12:23 matters. Fundamentally, this verse is related to the Jewish concept of pikuach nefesh (פִּיקוּחַ נֶפֶשׁ), or “saving a life.” Notice that the word for “life” is again “nefesh,” just as in Deuteronomy 12:23. In Judaism, pikuach nefesh, or the preservation of life, takes precedence over all other mitzvot. For that reason alone, Deuteronomy 12:23 matters — it matters because it instructs us about preserving life while consuming what we need to survive.

Another reason why Deuteronomy 12:23 matters can be found a couple verses later in Deuteronomy 12:25:

לֹ֖א תֹּאכְלֶ֑נּוּ לְמַ֨עַן יִיטַ֤ב לְךָ֙ וּלְבָנֶ֣יךָ אַחֲרֶ֔יךָ כִּֽי־תַעֲשֶׂ֥ה הַיָּשָׁ֖ר בְּעֵינֵ֥י יְהֹוָֽה׃

“…lo toch’lenu l’ma-an yitav l’cha ul’vanecha acharecha ki ta’aseh ha-yashar b’einei Adonai.”

“…you must not consume [the life with the meat], in order that it may go well with you and with your descendants to come, for you will be doing what is right in the sight of Adonai.”

In other words, by observing the mitzvah to consume ethically and sustainably and to work — both individually and collectively — to care for, nourish, and support both ourselves and those who are underprivileged, we can repair the world and make it a better place for us and for future generations.

Now that we’ve finished our Torah expedition for today, I’d like to leave you with some final words to consider — some metaphorical artifacts to take home with you (although please don’t remove artifacts from archaeological digs or from other communities in real life!). As we enter a new week and the new month of Elul, may we all cultivate a greater awareness of our own consumption and its impacts and consideration for how we care for, nourish, and support ourselves, those who are underprivileged, and this planet we all inhabit. May we all, individually and collectively, support each other in our work to consume more ethically and sustainably, to preserve life, and to repair the world and make it a better place for all of us who inhabit it now and for future generations.

Shabbat shalom.

![Life "[But] be strong to not consume the blood because the blood is the life and you must not consume the life with the meat." — Deuteronomy 12:23](https://cbiberkshires.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Digging-3.png)