God, and community, in the space between

The Israelites shall camp each with his standard, under the banners of their ancestral house; they shall camp around the Tent of Meeting at a distance. (Numbers 2:2)

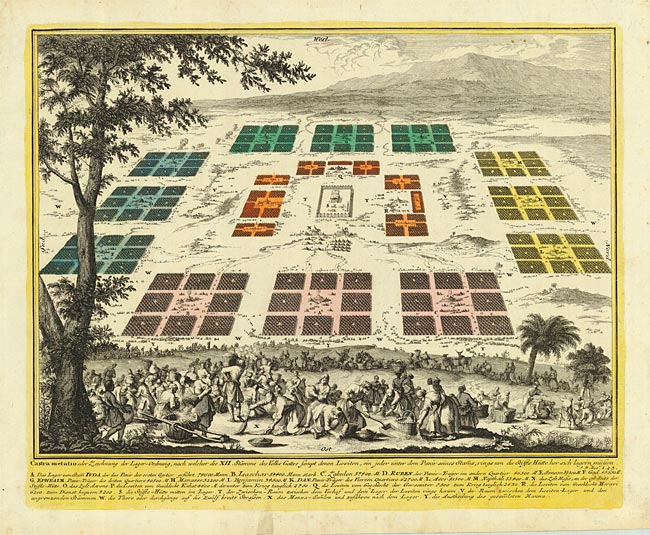

Tn this week’s Torah portion, Bamidbar, we read how the twelve tribes would encamp around the mishkan (the dwelling place for God) and the ohel moed (the tent of meeting). Each tent was at an appropriate distance from every other. In normal years, I’ve resonated with the idea that the tents were arranged at a distance to give each household appropriate privacy.

(That comes from Talmud, which explicates “Mah tovu ohalecha Ya’akov,” “how good are your tents, O [house of] Jacob,” to say that our tents were positioned so that no household was peeking in on any other. What was “good” about our community was healthy boundaries.)

This year, of course, the idea of camping at a distance from each other evokes the physical distancing and sheltering-in-place that we’ve all been doing for the past few months of the covid-19 pandemic.

Sometimes distance is necessary for protection and safety. Like our tents in the wilderness positioned just so. Like the physical distance between us now, each of us in our own home, coming together in these little boxes on this video screen.

But notice this too: our spiritual ancestors set up their physically-distanced tents around the mishkan and the ohel moed, the dwelling-place for God and the tent of meeting. The place of encounter with holiness, and the place of encounter with community.

Here we are, each in her own tent. This week’s Torah portion reminds us that our tents need to be oriented so that we all have access to the Divine Presence — and so that we all remember we’re part of a community.

When the Temple was distroyed by Rome almost two thousand years ago, our sages taught that we needed to replace the Beit HaMikdash — the House of Holiness, the place where God’s presence was understood to dwell — with a mikdash me’aht, the tiny sanctuary of the Shabbes table.

When we bless bread and wine at our Shabbat table, we make that table into an altar, a place of connection with God. That feels even more true to me now, as I join this Zoom call from my Shabbes table! In this pandemic moment, our home tables become altars: places where we encounter God and constitute community even more than before.

“Let them make Me a sanctuary that I might dwell among them,” God says. Or — in my favorite translation — “that I might dwell within them.” We make a mishkan so that God can dwell within us.

That feels even more true to me now too… as our beautiful synagogue building waits patiently for the time when it will be safe for us to gather together in person again. Until then, we need to learn to find — or make — holiness in where we are. We need to learn to find — or make — community even though we’re apart.

Our distance from each other protects us. And maybe more importantly, it protects those who are most vulnerable in our community: the elderly, the immunocompromised, those with preexisting conditions who are especially at-risk in this pandemic time. Pikuach nefesh, saving a life, is the paramount Jewish value. For the sake of saving a life we are instructed to do anything necessary, even to break Shabbat.

Being apart is painful and hard and it is one hundred percent the right thing to do — and the Jewish thing to do.

So we’re at a distance. So were our ancestors, as this week’s Torah portion reminds us. Our task is to make sure that our tents are positioned so that there’s space for God, and space for our community connections. So that God and community are the holy place in the middle. The place toward which all of our tents are oriented, toward which all of our hearts are oriented. Even, or especially, when we need to be apart.

Shabbat shalom.

This is the d’varling that Rabbi Rachel offered at Kabbalat Shabbat services over Zoom this week. (Cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)