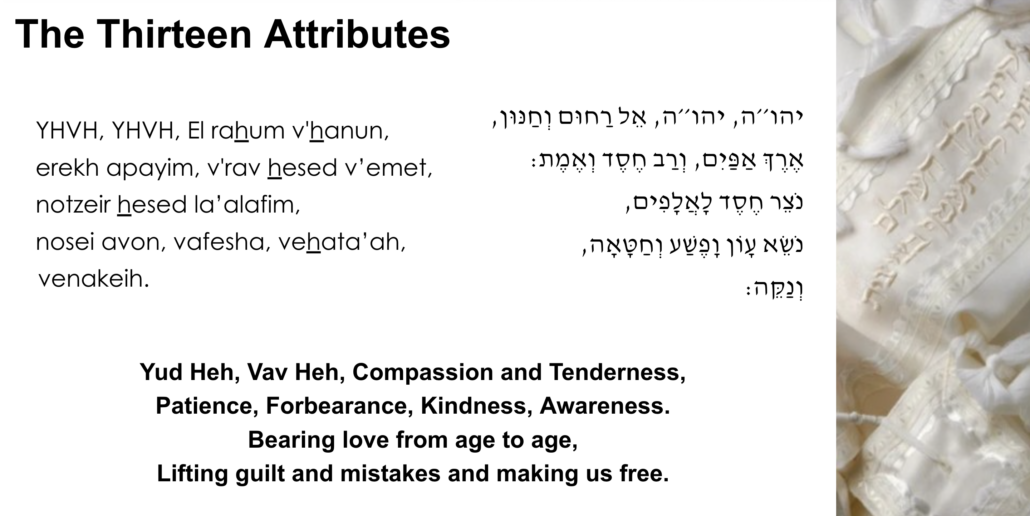

The Torah reading for this weekend is a special one that we read on the Shabbat during Pesach: Moshe asks to see God’s face. God says, “no one can see My face and live,” but makes a counter-offer: you stand in this cleft of rock and I will pass by, and you can see My afterimage. That’s what happens, and out of this story comes the passage we call the Thirteen Attributes, which we sing on Yom Kippur. In our singable English version, it goes:

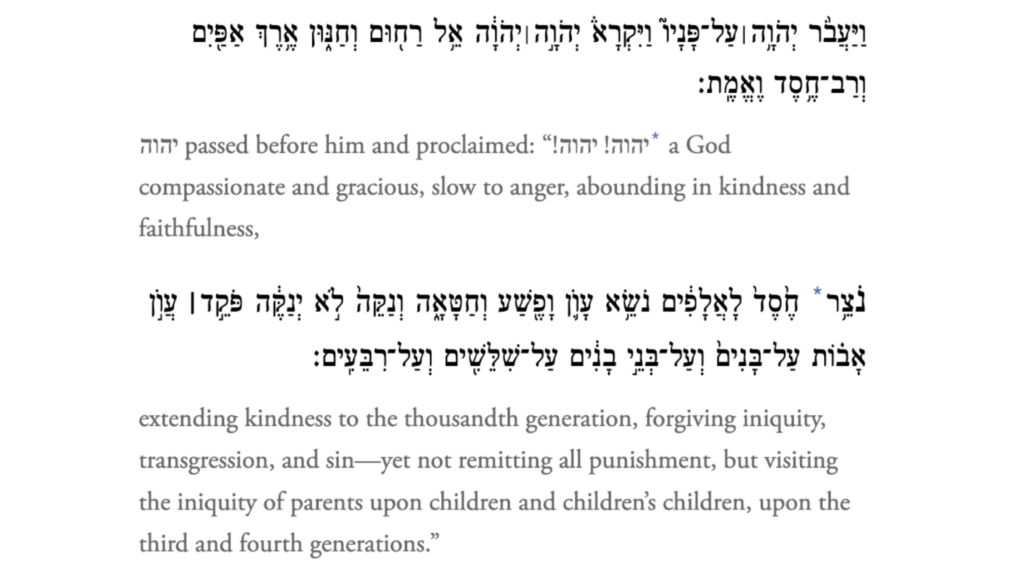

But some of you have maybe heard me mention that the version we sing on Yom Kippur is truncated from the original passage, which reads as follows:

Oof. Punishing children for the sins of the parents and grandparents, all the way out to four generations? I’m guessing some of us feel a little bit squeamish about that. That’s not how I want to imagine God! Here’s how I understand the verse, though. For me it’s not about God throwing lightning bolts of punishment at future generations. I see it instead as a description of how trauma works. When there is trauma, it ripples down through the generations.

I’ve been paying a lot of attention recently to how trauma flows through our lineage. In recent historical memory the biggest example is the Holocaust. For earlier generations maybe it was the Expulsion from Spain, or Portugal, or England… or Jerusalem, all the way back in the year 70… or Jerusalem, all the way back in 586 BCE when the first Temple fell. We carry layers of ancestral memory of persecution and tragedy, with the most recent ones on top.

The last six months in Israel and Palestine have activated a lot of inherited trauma. I know from conversations this week that many of us are activated by watching Free Palestine protests unfold on American campuses. Some of us may be remembering the Kent State massacre in 1970, feeling horrified at the sight of police officers facing off with students. Some of us may feel horrified by some of the pro-Hamas and anti-Israel slogans we may have seen in the news.

Anybody just feel a spike of adrenaline? My friend and college R. Jay Michaelson wrote a great piece this week about the stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol is the thing that allowed our ancestors to run from a sabre-toothed tiger. It’s also the chemical released in our brains and bodies when we read a horrific news story, watch an upsetting video, or confront anything that feels like danger. Today’s 24/7 news cycle can keep us awash in cortisol, if we let it.

I propose that we shouldn’t let it. It’s not spiritually healthy, and it’s not physically healthy, either. It’s the antithesis of Shabbat, which is one of the reasons I think Shabbat is so important and can be so sustaining. And it doesn’t actually help us, nor does it help anyone who is suffering in Israel or Gaza or anywhere. Instead, I invite us to go deeper into these words from this week’s Torah portion, because I think they hold a teaching that we need right now.

Torah here names God as compassion and tenderness, and patience, forbearance, kindness, awareness. What if we could bring those qualities to bear on what we’re seeing on college campuses – could we respond from a more productive and meaningful place? How about bringing those qualities to bear on the experience of reading and discussing the news? How about bringing them to bear on how we treat each other, and ourselves?

Made in the divine image, we can embody everything in this passage. Including the lines from Torah that we cut from our liturgy, the ones about blaming people for the sins of their ancestors. But the Israelis and Palestinians I admire most are the ones who turn away from that impulse, and I want to follow their lead. I want to strengthen kindness and awareness. And when we feel the impulse to lean into the litany of blame, we can turn toward our compassion instead.

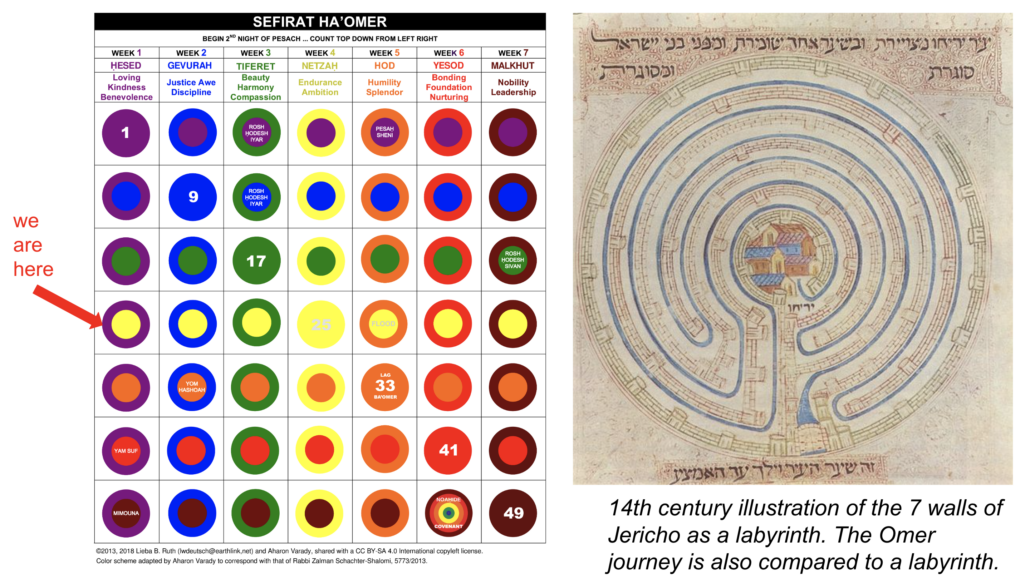

Speaking of qualities that we and God share, we’re in the first week of counting the Omer, the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and revelation. We’ll count in just a moment. The quality our mystics assigned to the day we’ve just begun is netzah, endurance, within the week of hesed, lovingkindness. Today is a day for cultivating not only our lovingkindness, but our capacity to make that quality last.

May this day of netzah she’b’hesed strengthen us in bringing enduring kindness to ourselves, to each other, and to the world.

Shabbat shalom.

This is the d’varling that Rabbi Rachel offered at Kabbalat Shabbat services (cross-posted to Velveteen Rabbi.)